*English for Today*

*Nigerian English and the English Language in Nigeria: Putting my Lessons in Perspective*

Ganiu Abisoye Bamgbose (GAB)

As I resume my English for Today series, it is essential to make some clarifications on the focus of my lessons, especially in line with the status of the English language as a second language in Nigeria.

Many have argued that my formalist approach to language teaching in the cyber space is discouraging to the growth of a Nigerian variety of English. This essay therefore sets out to shed light on this as I begin my daily lessons this year.

The English language is incontrovertibly the most prestigious language in the world. It is the most geographically dispersed language and over fifty percent of the world literature are made available in English. The international status of the English language and its wide spread has resulted in the emergence of national varieties across the globe; hence, the nomenclatures: Canadian English, Singaporean English, Indian English, Ghanaian English and of course, Nigerian English.

Nigerian English is a variety of English which captures the sociocultural realities of the Nigerian people. It captures their peculiarities and worldviews. The present state of Nigerian English can be compared to the work experiences acquired by a Nigerian undergraduate. The reality is that such experiences will not likely be reckoned with formally in most workplaces since such were acquired before graduation. In the same regard, until there are books that address what constitute Standard Nigerian English and the usages therein reckoned with by government policies as official and appropriate ways of writing, Nigerian English must still be taught in close relation to its mother variety; the British English.

Standard is a universal linguistic concept which applies to all world languages. Even the British English we toe its path has its standard variety. The interesting thing however is that the standard variety of any language is often used by less than 20% of the populace. Even in England where English seems to be the only existing native language, only about 15% speak the language in its standard form.

Taking clue from Yoruba, one of the West African languages spoken in Nigeria, it amazes and amuses even adult speakers of the language when they find out that certain expressions that they have used for years are rendered in nonstandard forms. In his inaugural lecture, a professor of English, Adeleke Fakoya, gave the etymology of certain names of places that are now wrongly articulated. Two of such places in Lagos are Magodo and Alausa that originally mean “do not pound” and “where walnuts grow” respectively. Most Yoruba in Nigeria pronounce these names wrongly now and many get amused when they are informed of how these words should be pronounced. Similarly, a Yoruba proverb says: Nǹkan tó wà lẹ́yìn Ọ̀fà, ó ju Òjé lọ (meaning what lies after the town of Ọ̀fà is much more farther than its neighbouring town called Òjé). This proverb is often erroneously rendered by many Yoruba as nǹkan tó wà lẹ́yìn ẹ̀fà, ó ju èje lọ (what lies after 6 is more than 7). The point therefore is, if as Nigerians we have issues keeping in touch with standard expressions in our native languages, it is pertinent therefore to subject ourselves to constant effort at maintaining standard in a foreign tongue which is not just a language but our language of official transactions, upward mobility and international repute.

My lessons are therefore not in anyway detrimental to the growth, nativisation or indigenisation of the English language in Nigeria. It is just an effort at keeping us in proximity to the standard variety which we are affiliated to; the British English. This is because anyone who will deviate from a norm needs a sound knowledge of such a norm. We can only grow our variety of English called Nigerian English when we situate it well within the context of the British English by understanding the realities of our world which are not captured in the mother variety.

Nigerian English cannot, should not and must not be a bastardisation of a well documented variety of English and should not be a hybrid resulting from our misunderstanding and misconceptions from the two leading varieties of English: British and American Englishes.

My lessons are therefore an effort at teaching the English language in line with international standard usages to ensure that we can communicate and be communicated with by all users of the language across the globe.

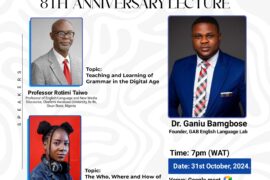

*Welcome to GAB ENGLISH LANGUAGE LAB in the new year!* I shall dish out my lessons daily paying attention to just two confused or misconceived usages among Nigerians in each lesson.

You can follow me @:

Gani GAB Abisoye Bamgbose and GAB ENGLISH LANGUAGE LAB (Facebook)

@GaniuBamgbose (Twitter)

www.englishdietng.com (Website)

Or a personal encounter on WhatsApp: 08093695359

(c) Ganiu Abisoye Bamgbose (GAB)

University of Ibadan

3 Comments

Well done, GAB. More grease to your elbow.

To say “more grease to one’s elbow ” is also non standard variety of English. Rather, in standard form , you can say “more power to your elbow ” .

Please, what is the difference between wake keep and wake keeping and which is correct